If my blog traffic statistics tell me anything, it's that you are probably reading this after a google search related to your interest in the opening of the John Peel Archive online. My original piece, written when the project was announced in February 2012, appears below. If you are an ardent Peel fan, you might want to scroll down now. If you have an true interest in music and scholarship, hear me out.

[Image: John Peel and collection, date unknown.]

The Peel Collection made its debut this week with the first 100 titles in the alphabetized A section. 100 more titles are scheduled to be added each week. The site is well-produced, with photos and videos in addition to the record collection. I'll restrict my comments to the experience of browsing the records.

It is a hollow experience, a faint shadow of the project's potential. As a visitor, you are confronted with a photo of album spines. As you mouse over the spines, a popup appears for each, with a thumbnail of the album cover and a "card" (catalog?) number. Curiously, the cards are not numbered 1-100. Click on a spine and the corresponding "card" appears, with photos of the front and back cover, additional photos if the album has more elaborate packaging, and an image rendered to look like an index card with the track titles.

That's it.

Oh ... and a link to hear audio from the album on Spotify. Assuming, of course, you have a Spotify account.

The physical collection is a priceless one-of-a kind significant object, given its size, its owner and its place in the history of poular culture. Separate any one phsyical album from the rest of the herd, and it becomes just another used record, with a market value governed by scarcity and condition. Reduce it to a Spotify playlist and it becomes an infinite object with zero value.

Anyone can make a playlist of songs that happen to be in John Peel's collection. With 25,000 LP titles in the collection, it's hard to make a playlist (of songs released prior to Peel's death) that doesn't contain something from the collection. So the "musem" contains photos of metadata (not metadata itself), and weblinks to existing MP3 files. All of which can be gathered from other sources, often in more depth, via online search.

We were promised original paintings. Instead we got a xerox of a Poloroid of a photo of a painting. The site will always attract the mere curious for a single visit. But it offers nothing of permanent value. I don't see the project getting past the C's before the sheer futility crushes the will of all involved. Its celebration in the blogosphere and twittersphere (I haven't found a second dissenting opinion) are further examples of how we are all losing respect for knowledge in general, and music in particular.

Thanks for reading.

[Original essay below.]

The LP collection of the late BBC radio host John Peel, more than 25,000 titles, is going to be digitized and made available to the public via an online museum. This provides an opportunity to discuss the inherent value of physical and digital media as it relates to scarcity.

Physical media — books, LPs and the like — are scarce objects. No matter how many are made, the number is finite, the individual objects are unique, and are subject to wear, damage and loss over time. The ones that survive retain value according to their condition.

Digital media — information stored in bits-only form — are infinite objects. There is no limit on the number of people who can simultaneous possess the information, each copy is identical, and does not degrade over time. The value of infinite objects is in the information transfer; the objects themselves have no retained value.

Attaching infinite objects to scarce objects can make those scarce objects more valuable. Some examples:

- Unlimited streaming of the movie Clueless (infinite) has helped cement Jane Austen's position as a literary icon for another generation. This in turn elevates the value a certified first-edition copy of Emma (scarce).

- Reports show digital downloads of Van Halen's A Different Kind of Truth (infinite) are not selling well, but music industry veteran Bob Lefsetz offers this view: "Based on [fan] reaction, the band will be able to tour for years." (Concert tickets: scarce.)

- A high-resolution digital transfer of a rare LP, taken on the owner's own equipment calibrated to his exact specifications, allows the LP's content to be shared, studied and enjoyed without inflicting further damage. The scarce object becomes more significant by being both widely accessible (infinite) and perfectly preserved.

Which brings us to the Peel Museum project. A physical music collection as large as the Peel is beyond scarce — it's one-of-a-kind. Its value to a private collector is enormous, but finite. There would be a winning bid at auction, the public would gasp and tweet at the figure, and then the collection would disappear into a vault somewhere, never to be seen again until the next auction (and almost certainly never played).

By having the collection digitized and made freely accessible to the public, the Peel family escalates its status from significant object to priceless cultural landmark. Bravo.

What would I want produced by the project? Three things:

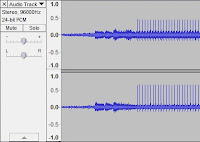

- A high-resolution (at least 24-bit/96KHz) digital transfer of each album and single in its current condition, representing the archive of the collection.

- A high-resolution digital restoration of each title, producing the highest possible sound quality that can be achieved from the archived copy. These are the versions that can be made accessible for social, educational, historical and scholarly projects. New restorations can be created as technology improves, as new tools and techniques become available.

- Creative ways for the public to browse the collection, its cover art, its label art, search its metadata, and listen to audio (where not restricted by copyright).

What would you like to see produced from this landmark project?

Artist: Wynton Marsalis

Genre: Jazz

Year: 1983

Artist: Wynton Marsalis

Genre: Classical

Year: 1983

Wynton Marsalis scored a landmark achievement in 1983, winning both the Best Jazz Album GRAMMY® for Think of One and the Best Classiscal Album GRAMMY® for Trumpet Concertos. Acquisition of these titles on LP over 30 years ago began for me a personal interest in Mr. Marsalis' work that continues to this day.

© 2012 Thomas G. Dennehy. All rights reserved.

.jpg)