|

| Metadata indexes and catalogs your music library. |

These are hard-won bits. After you've carefully repaired old wear-and-tear, meticulously isolated and labeled all the tracks, and studiously supplied metadata, it's hard to dismiss your newly-ephemeralized title as just another entry in the library.

In contrast, ripping a CD is a mindless task. There are now robots available to do it for you, stacks of discs at a time. Downloading titles has become so easy their arrival has little impact. After purchasing Kate Bush's 50 Words For Snow on high-resolution download, I had to remind myself a week later that the bits had yet to be played. I can't imagine that kind of detachment after finishing an LP transfer, just as I feel more invested in a meal prepared from scratch than I do ordering takeout.

Metadata are the fields — Artist, Title, Genre, Release Year, etc. — that enable media players to index and catalog a music library automatically, providing constant-time access to all songs, no matter how large the collection. Virtually all CD ripping software has access to an online metadata source to supply the basics. In ephemeralizing LPs, the job of completing metadata falls to you, and the necessary time investment pays off.

Metadata are the fields — Artist, Title, Genre, Release Year, etc. — that enable media players to index and catalog a music library automatically, providing constant-time access to all songs, no matter how large the collection. Virtually all CD ripping software has access to an online metadata source to supply the basics. In ephemeralizing LPs, the job of completing metadata falls to you, and the necessary time investment pays off.In addition to the basic fields, jazz aficianados routinely complete the Contributing Artist field for a song (not universally available in online metadata sources) to track the dynamics of musicians moving from combo to combo. Enhanced metadata libraries with many extra fields for classical music are becoming available. Using metadata, collections can be sorted along any of the fields.

Yet, armed with all this information, I still can't sort my collection autobiographically — chronological by acquisition date. That information is deeply personal and uniquely revealing.

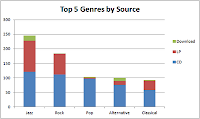

Imagine being able to go back and revisit your purchases, deduce what prior purchases or other factors influenced each decision. Did you buy artist B because s/he previously played with artist A on a title you liked? You could see exactly when particular artists came into your consciousness, or left it. An animated graph of the top 5 genres in your collection over time could show how your tastes evolved. The autobiographical sort would reveal more than any other slice through a person's library.

I'm sure there is someone reading this who has kept that information. In what personal ways do you catalog your music collection?

Artist: Arthur Blythe

Genre: Jazz

Year: 1982

How did this album find it's way into my library? It would be a complete mystery unless you study the metadata. Most likely I sampled Arthur Blythe as a bandleader because he recorded as a sideman with Jack DeJohnette's Special Edition. Mr. DeJohnette, a 2012 NEA Jazz Master, is for me a trusted source due to his long association with Keith Jarrett and Gary Peacock in the so-called Standards Trio. But Mr. Blythe's presence in the library was "one and done," so Elaborations clearly didn't suit my taste at the time of acquisition. It may be a better fit now.

Genre: Rock

Year: 1974

It wasn't until I ephemeralized this title, a birthday gift long ago in high school and long out of heavy rotation, that I realized that it contained the song, "Time Waits For No One." As an amateur creator of WDET-FM Music Head playlists, — which connect the metadata dots among songs — and restricting said lists only to content in my own library, I long sought to make the leap from artist Tom Waits to title, "Time Waits ..." And now I can.

© 2012 Thomas G. Dennehy. All rights reserved.